Cde Aguil Chut - A nation mourns the passing of Africa's Mother Teresa and a female warrior

- Bold Magazine

- Jun 18, 2022

- 6 min read

Freedom fighter Aguil Chut Deng, who fled to Toowoomba, Australia is to be buried in South Sudan’s Heroes’ Cemetery at the president’s behest.

Aguil Chut Deng’s life was one of bullets and beatings as she became a beacon of hope.

Death circled Deng and her family on the blood-soaked soil of Sudan, a memory almost too far removed from their adopted Australian homeland to be real.

Half of Deng’s life was spent in Africa, but in her later years, the 54-year-old called the Garden City of Toowoomba home.

Now, a funeral will be held for the freedom fighter on Saturday in the state’s south-east, before her body will be flown back to South Sudan, where she will be buried in the Heroes’ Cemetery on the president’s wishes.

The “mother of Sudan”, Deng was Africa’s Mother Teresa – “a man in a woman’s body”.

That’s how her younger brother, once a child soldier in Sudan, remembers her.

Ayik Chut Deng – or Daniel as he’s also known – is solemn as he sits on a couch across from his sister’s son, Dut, in Brisbane.

A former soldier in the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), Ayik has just returned from the fight to save Ukraine. As the sun shines through the curtains of his nephew’s home, he talks of burning bodies.

His decision to take up arms against the Russian invasion is one he thinks his sister would be proud of, and something she would have done to save the millions of refugees.

As missiles rained down on him while he rushed to bunkers in Western Ukraine earlier this year, he thought of his sister, some 13,000 kilometres away in Toowoomba.

She had gone missing in April. It would later be discovered that the mother-of-four had taken her life.

“I wish I did die in that time I was bombed in Ukraine, instead of her,” says Ayik, his eyes dark with the unspeakable horrors of multiple wars.

“When I came here, I said, ‘Why? Why did I survive that?’ Because if I did die, she’d be mourning me.

“If I did die on that day, she’d be mourning me and then killing herself because I know the passion she has.”

Ayik’s young daughter, Sunday, 3, springs happily around the room as her father and cousin talk of death.

It is her generation, Dut says, that his mother was trying to save. The youth, both in Australia and Sudan, were the keys to the future.

Deng was constantly working with people in Toowoomba and Brisbane, and before the coronavirus pandemic, had frequently flown to Sudan to help the displaced.

Dut says his mother was in every community meeting, every government meeting, every meeting where she thought change was needed.

Comrade Deng, as she was referred to in a title typically only given to men, is lauded across the globe for her passion as a fierce revolutionary.

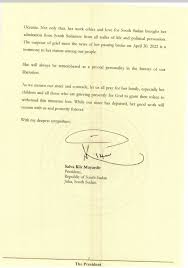

The president of South Sudan, Salva Kiir Mayardit, says she was a “pivotal personality in the history of our liberation”.

Deng will now be buried in the nation’s Heroes’ Cemetery. It will be the first time Ayik has returned to the war-torn country in 26 years.

However, Deng’s work is so widespread, her family still don’t know all that she accomplished.

They know she helped establish a referendum voting system in South Sudan, worked with thousands of refugees and women to improve their lives – both in Queensland and South Sudan – and saw the best and worst of humanity as she rescued people from conflict zones.

Friends recalled that in February, Deng helped police communicate better with African youths in Zillmere, in Brisbane’s north, following a spate of unrest.

Whether it was in Toowoomba or war-torn Sudan, she acted when change was needed.

Ayik says his sister’s drive sprang from her upbringing, in which she was disrespected for being a woman and was often beaten. From there, she found the courage to begin her campaign for change.

The pair were born into a large, multi-faith Dinka family in southern Sudan, where Deng overcame oppression, poverty and illiteracy – with the added disadvantage of being a woman.

As the beginnings of the 1984 civil war crept into every corner of their lives, Deng watched as millions of people were killed and displaced. She thought of her family, and her people. She thought of what the future held.

About that time, in her early teens, she told the SPLA she would join them. Although she was ridiculed for being a woman, her skills with medicine – picked up from watching her father, a doctor – enabled her to prove her worth as she treated the wounded.

Constantly on the run in the bush, Deng heard rumours of a refugee camp across the Ethiopian border and decided to take her clan to relative safety there. She braved enemy fighters and landmines for months across treacherous terrain, all the while thinking of how the nation’s children would be educated – the one thing she believed could save them from history repeating.

The United Nations estimated at the time that the refugee camp had a population of more than 200,000, with more than 30 people dying a day.

But Deng continued to return to the front line to help the rebels. Along the way, she was separated from Ayik, who regularly moved with the SPLA.

It was only in 1996, after Deng had rejected several offers of asylum from other countries because they would not allow her 12-strong family to travel with her, the group was accepted into Australia. Theirs was one of the first Sudanese families in Toowoomba.

Ayik recalls seeing his sister withdrawn and uncommunicative in Toowoomba; at other times, she was upbeat. The family says, in line with the African way, she kept much to herself, including when she was in prison.

“I feel like my sister had that trauma from the past. She’s been in a lot of places. After the soldiers captured a place, she’d be there,” Ayik says.

“She always liked to go straight away and work with women.

“She was arrested a few times when I was getting trained as a boy soldier ... I remember I used to walk two to three kilometres to take food to her at night, and walking there, there were hyenas, leopards – we’re in the jungle, nowhere was safe.”

In Queensland, as Dut put up posters about his missing mother, he was approached by strangers who said they knew her. She was someone who touched the lives of everyone.

Ayik and his nephew are similarly warm-hearted, the type to shake your hand with both of theirs and give you a hug. Their problems are no more important than yours.

But Ayik, who was wrongly diagnosed with schizophrenia, says his sister would have struggled with the same dark flashbacks that linger in the corners of his mind.

War defined them on the outside, but also lurked as a constant internal battle.

His memories are littered with moments of his hands in a vice-like grip around a gun, which often presented as the only solution to a fractured world ridden with bullet-torn bodies.

“She saved my life by taking me out of the army. As a boy soldier getting trained, I became very angry,” says Ayik, his voice dropping.

“The way I was trained by the bullies, when I had my gun in my hand, anyone who mucked around with me, abused me or anything, I walked into the room like I’m going to get something, and I’d come out with a gun. I even pulled a grenade on people.

“People had to beg me to ‘put it down, put it down – you’re gonna kill all of us!’ ”

It is that world, so different to Toowoomba, that Deng’s family suspects she was thinking of as she spent her final hours buying groceries on Australian soil not blackened by the blood of millions of civilians.

The family is shocked to see so many African families in the regional city now. When Ayik visits, he smiles as he sees an African woman carrying a cross as tall as her down the street. He doesn’t offer her a lift as he would in Africa, joking that in Australia, it might look like he was trying to kidnap her.

But the single father does pause as he ponders whether the town knows he’s not just a visitor but one of the originals.

Arguably, his family has done more for Australia than most people.

And Dut hopes to complete his mother’s work and make the world a safer place, by pushing to get one of Deng’s final projects through: a youth centre.

“She had a good heart. She just cared about the world – every single person. This was her thing,” he smiles.

“She didn’t believe in hate, she didn’t believe that existed. Second chances, third chances, everybody deserved a chance.

“Make a change – she just believed that her whole life. Just love.”

Source: Cloe Read from Brisbane Times, Australia

.png)

.png)

Comments